Refugees

It sounded like knocks at the door, but I doubted. I did not think any sensible people would leave their house under the ongoing rainstorm and thunder that crashed one after another. They had begun since the Sisters brought me dinner. The crackling and flapping tin roofs were eerie; the shaking house kept me awake and nervous; I let the door unlocked in case the house suddenly crumpled. But the knocking sound became clearer.

“Who is it?” I yelled from my bed on the floor. No answer. The knocks turned into the bangs. I dragged myself toward the front door, but was staggered seeing—through the glass window—so many people in front of my house.

I opened the door. “Our houses almost fall down. All roofs and walls have flown,” one of the visitors said. Behind me, under the rain, I heard the children crying. The yard had become a pool; just about 15 centimeters higher, the water would enter my house. All young children were either on the shoulders of the adults or in the dugouts.

“All go to the hospital,” I told them. The hospital just about three meters to the left of my house. Thanks, God, its floor was still dry. The alley had been full of people. “You go to the convent and call the Sisters,” I pointed a man in the crowd.

Four Sisters came. I asked them to open all wards and the waiting room; wards for the women and young children; the waiting room and alley for men and boys. “Ask Sister Albertina to boil water for sweet drink for them,” I said to Sister Priscilla. Albertina was the kitchen Sister, a very old one.

With a dugout, Sister Pai, Priscilla, and I went to the village. Rowing in the darkness and under heavy rain was hard. Bayun had merged to the Arafura Sea. We were moving between coconut trees. The dugout was swaying caused by nervous passengers and finally turned over in front of the school.

The Sisters screamed before jumping into the water—chest high to me, neck to them. We held to the upside down dugout. Cold and wet, but then we laughed at our hopelessness with the dugout. Together with the rower, we turned back the dugout and pushed it toward the school. We climbed up the school floor and returned into the dugout, which was not easy for the Sisters with the robes on.

All houses were damaged; some had been flat. I entered the houses and calling people and flashing around with my torch. It was very dangerous because anytime the houses could collapse. It seemed all have been in the hospital.

Everybody had hot drink when we returned in the hospital. It was about ten o’clock. I went home, picked up all my cookies, and gave them to the young children. Then something came up into my mind. It was an ideal time to do filaria survey. All people in the hospital all night.

I picked 100 people to be my survey subjects. I punctured their fingers every two hours three times for the blood smears. That kept me busy all night. The men returned to the village at dawn, the women and children a few hours later.

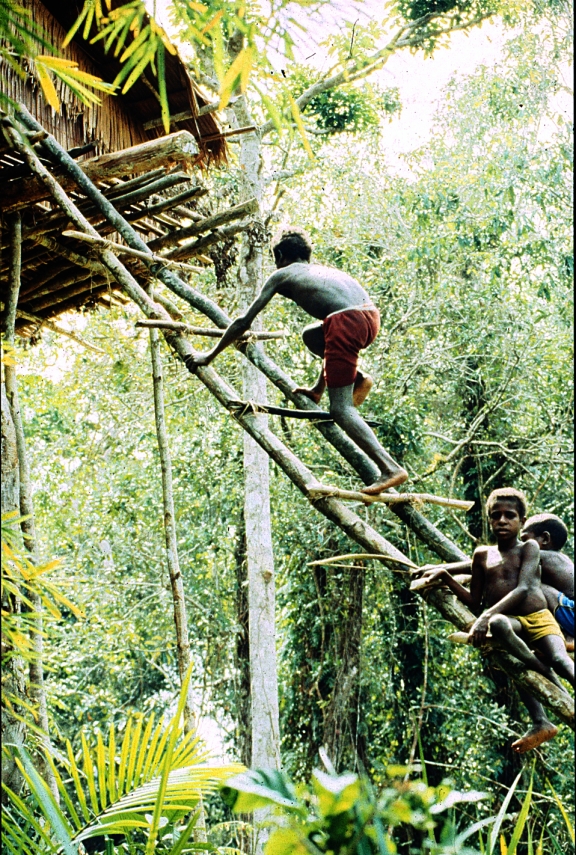

All but one house were ruined. The survived house belonged to Dasih; my old friend, again, showed his distinguished achievement. He had built the house with much better material, design, and location—farther from the waterline. However, the Asmat were robust. Within three days, they finished rebuilding their houses with sticks and palm leaves, which did not look better than the old ones. House is just a place for cooking and sleeping together—6 to 10 families; it is not worthy to work hard—they did not have to buy the abundant material around them—to build a good one. Perfect philosophy for the hunter-gatherers.